By Olakunle Osisanya, fdc.

At a security conference organized by the National Assembly on Tuesday, 3rd June, 2025, the Chief of Defence Staff (CDS), General Christopher Musa, made a presentation which among other things, recommended the fencing of Nigeria’s land borders to curb insecurity.

Apparently, due to the frustrations with the never-ending Boko Haram insurgency and banditry across Nigeria, the idea of a border fence resonated with the public. A short video of the CDS promoting the idea was widely circulated on social media, with examples from the Pakistan/Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia/Iraq borders. Thereafter, the proposal has attracted conflicting opinions, and the debate remains in the public domain.

To place Nigeria’s security challenges in proper perspective, one needs to understand the size of the country. Nigeria covers an area of 923,768 km2, comprising densely and sparsely populated areas. However, large portions of the hinterland, including national parks and forests, are devoid of government presence, policing and basic infrastructure. This, therefore, creates a conducive breeding ground for violent non-state actors.

In a BBC Hausa Service report on 19th July, 2021, the editor, Aliyu Tanko, categorized Nigeria’s security challenges as jihadism, herders-farmers clashes, banditry, kidnapping, separatist insurgency and oil militancy.

Currently, policing in Nigeria is exclusive to the federal government. At a recent presentation at the National Institute for Policy and Strategic Studies (NIPSS), the Inspector General (IG) of Police, Mr. Kayode Egbetokun stated that the Nigeria police to citizen ratio stands at 1-650, as against the UN recommended 1-460 persons. This shows that Nigeria is under policed, despite being faced with a myriad of security challenges that threaten national security.

Historical accounts reveal that the act of fencing settlements is as old as human civilization. Following the realization of the benefits of communal life, the urge for protection became paramount; hence, communities identified perimeters to be reinforced to keep out wild animals and invaders. Examples include the Greek mythology of the Trojan horse which breached the fortified city of Troy, the Great Wall of China; meant to deprive herders north of China from invading farming communities, and the biblical story of the wall of Jericho. In recent times there was the Berlin wall, which separated East/West Germany in the Cold War era. Today, there is the America/Mexico border wall, the Israel/Gaza wall, and the Kenya/Somalia wall. Nigerian towns also have a history of defensive walls and gates, such as the ‘kofars’ of the north, the Benin-City moat, and border guards “asobode” in Yoruba land. Thus, the idea of fencing Nigeria’s land borders is not novel.

A study of Nigeria’s geography would reveal a climate and vegetation that extends northwards from the Atlantic ocean through coastal swamps, rainforests, and terminates at the Sahel savanna.

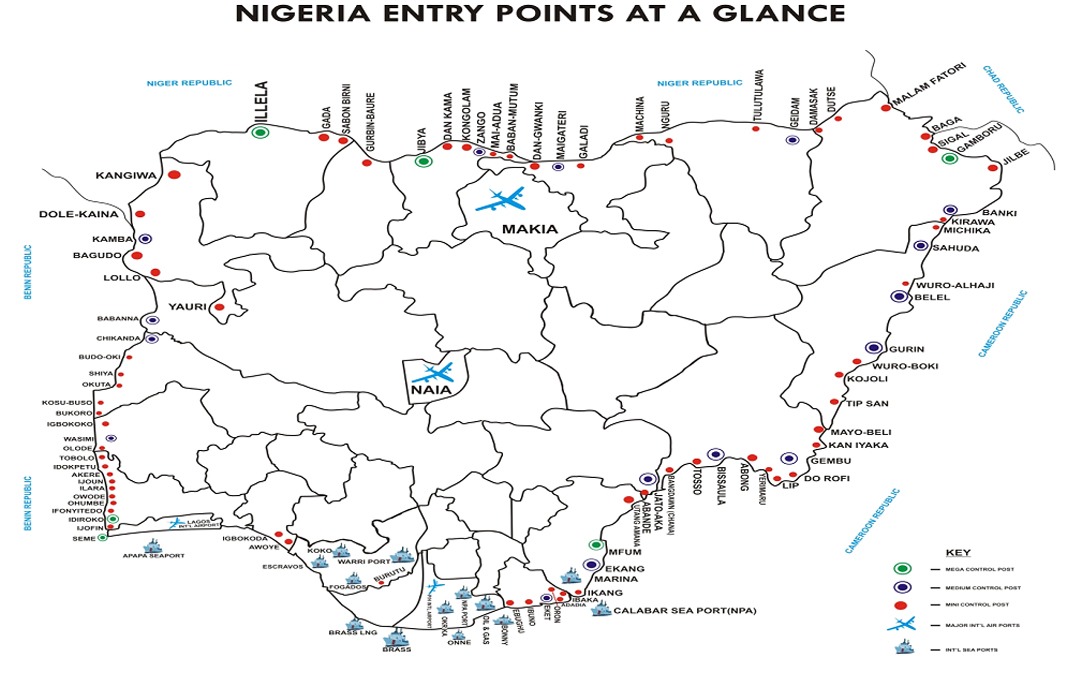

To the west, the 809 km border with Benin Republic cuts across the entire vegetation range. To the north, the 1,608 km border with Niger Republic runs eastwards, across the Sahel, terminating at the 85km border with Lake chad, in Chad Republic. To the east, the 1,975 km border with the Cameroun ranges from the coastal swamps through the rainforests up to the Sahel. However, it is affected by the Mandara mountains and Mambila plateau, with largely rugged terrain and relatively low temperatures. Nigeria’s over 4,400 km of land borders, therefore, consists largely of terrain devoid of natural physical barriers to prevent easy access and is therefore fairly porous.

Europeans partitioned Africa without regard for preexisting ethnic groups, kingdoms, and borders. The colonial boundaries sliced through homogeneous communities, families, farms, and structures, dividing them into separate countries, and conflicting administrative systems. Suddenly, kith and kin at border communities found themselves in different countries, and became entangled in divided loyalty and national affiliation. The situation was further compounded by the deprivation of basic social amenities, like schools, hospitals, markets, good roads and public power supply, leading to feelings of marginalization. This further negatively impacted their sense of patriotism. An attitude which is still prevalent to date.

Despite these colonial divisions, the historical, social, and cultural bonds of the various indigenous peoples remained intact. These include intermarriages, shared religious and cultural ceremonies, and subscription to the sovereignty of traditional authorities across national boundaries. A former Nigerian president, once famously announced his preference to spending his retirement in Niger Republic. Thus, loyalty to cross-border affinities as against loyalty to national boundaries remain very strong.

Economically, the historical trans-Saharan trade and trans-Atlantic slave trade were precursors of current formal and informal trade around Nigeria’s borders. Exchange of grains, spices and foodstuffs, cash crops, livestock, fishery, and leather subsists. Furthermore, Nigeria spearheaded ECOWAS and is prominent in the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) to promote African trade and integration. Thus, trade and economic relations across Nigeria’s borders, remain strong.

Despite legitimate trade, the serious economic disparity between Nigeria and her neighbours, creates another problem, which compounded by the differences in currency exchange rates of the Naira and CFA. This incentivizes illegal cross border trade like smuggling of contraband, especially fuel, small arms and light weapons, smuggling of migrants, narcotics, rare and precious minerals.

Beyond Nigeria’s borders, the advent of climate change and the damage to agricultural productivity across the Sahel region, also gave rise to competition for diminishing resources, which leads to conflicts, worsened by the proliferation of illegal arms. To escape the environmental devastation, large civilian and militia populations migrated southwards, choosing Nigeria due to its perceived liberal disposition and shared ethno-religious affinities. Sadly, the entry and integration of these foreigners was grossly mismanaged by the political, tribal and religious leaders in Nigeria. Many of the migrants who were already involved in rebel activities became a thorn in the flesh of citizens, as well as ready recruits for criminality in Nigeria.

The agencies that are mandatory at recognized land border control posts include; the Nigeria Immigration Service (NIS), the Nigeria Customs Service (NCS), the Port Health Services and the Nigeria Agricultural Quarantine Service, complemented by others. According to the NIS Annual Report, 2019, there are 114 land border control posts and 72 border patrol bases; however, there are over 1000 illegal routes.

The average distance between each control post is, therefore, approximately 39 km of mostly ungoverned spaces. About 500 border security agents holding hands in a straight line would be required to cover just one km. Therefore, the current staff strengths, technology, and logistics fall short of requirements. Also, inter-agency rivalry is rife. Therefore, the capacity for effective border security management of Nigeria’s land border is compromised by inadequate manpower, and logistics, as well as poor inter-agency collaboration.

The ongoing Lagos-Calabar highway is projected to cost N4b per km by the Hon Minister of Works, Engr David Umahi. Adopting this template, the possible cost of compensations, construction and finishing of a solid border fence around Nigeria, over a distance of 4,400 km, would cost over 17 trillion naira, and may last several years before completion.

I wish to conclude with the following;

a) In spite of some reported acts of criminality, normal human activities still dominate Nigeria’s border areas. Therefore, in the absence of empirical evidence, a correlation between fencing the borders and ending insecurity in Nigeria has not been established;

b) Given the projected cost of N17tn, coupled with the state of the economy, the construction of a border fence might prove too expensive and time consuming for government, and is unlikely to attract private sector participation;

c) A border fence will further divide border communities and may instigate socio-cultural and diplomatic resentment, thereby making such fence prone to vandalism;

d) Based on the deductions at the end of some of the preceding paragraphs, it is doubtful whether a border fence would make any significant difference in ending insecurity in Nigeria.

In addition to the support of our Armed Forces, I, therefore, recommend;

i. Improved budgetary allocation for socio-economic infrastructure at border communities;

ii. Recruitment of more personnel, improved human capital development, enhanced technology, and additional logistics for the mandatory border agencies, along with capacity building for better collaboration;

iii. Approval of realistic remunerations for border security officers. This will go a long way to indicate government’s commitment to combating economic sabotage and other common crimes around the borders;

iv. Possible review and, or decentralization of the current border security architecture, in line with emerging best practices. For example, the USA has separated Customs and Border Protection(CBP), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and Border Patrol Officers, among others.

v. Increased government presence in the hinterlands, through the provision of basic amenities in rural settlements near identified ungoverned spaces. This would discourage rural-urban migration.

vi. Decentralization of policing to all jurisdictions and levels of governance in Nigeria, to be followed by significant recruitment of new personnel and human capacity development;

vii. Reform and decentralization of the National Parks Service to all levels of government in Nigeria, to be followed by increased budgetary allocation for procurement, staff recruitment, training, and deployment of Forest and Park Rangers.

Olakunle Osisanya, fdc, is a retired ACG, of the Nig. Immigration Service. He can be reached at olakunleosisanyag@gmail.com